AFTER twenty miles of desert track, the light grey tone Land Rover comes to a complete halt.

The men in khaki are quick to jump out and take a look around - They’re sweating.

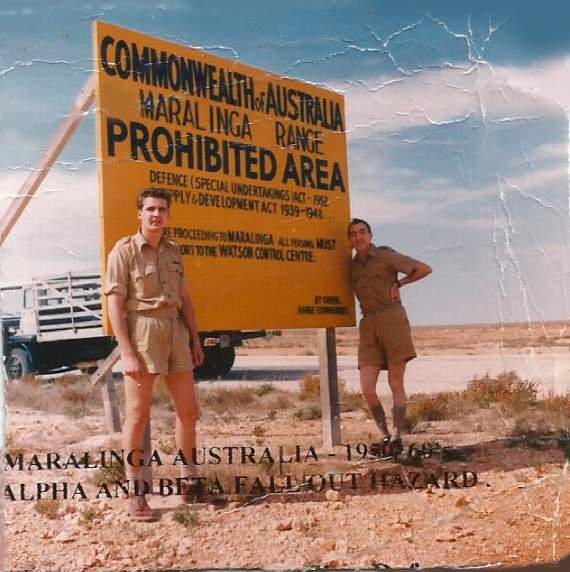

They can see damaged tanks and abandoned aircraft in the hazy distance. But this isn’t a warzone. It’s an experiment site. It’s 37 degrees centigrade and then men are in Maralinga, Australia. It’s March 1965.

Dennis Hayden, a 21-year-old junior technician with the RAF has just arrived for his year long stint at the South Australian nuclear test site.

The ranger leading the expedition encourages the men to look into the 30-foot bomb crater and encourages them to climb into it. “It’s perfectly safe” he told them.

This was the first thing new arrivals at the base went through. They were shown the craters from the atomic blasts that had taken place there.

“We used to travel across the desert to Emu, one of the other test sites, and would camp out there.

"We had no idea of the harmful effects from the radioactive particles that could be there.

“There were many dust storms while I was there and everything would be covered in a thin layer of dust. We were breathing it all in.

“None of the military were given respirators. Only the scientists that went into the craters were seen wearing protective gear.

Mr Hayden had to leave the base before concluding his year long stay due to an acute inflammation of his eyes.

“After 11 months my eyes became inflamed and the local medical officer didn’t know what to do so I was sent to a Royal Australian Air Force hospital some 500 miles away and I was diagnosed with acute iritis which was caused by exposure radiation.

“I was taken to Adelaide and the nurse told me that loads of men came down from Maralinga with all sorts of health problems,” he said.

Mr Hayden, now 71, lives in Lydney and is campaigning for the government to award war pensions to nuclear veterans, their widows and descendants.

“Nobody was aware of the danger. We were all lead to believe it was completely safe. I thought the idea of going into the crater was silly. I just stood at the top and looked in.

“The whole thing was a big experiment. It was testing the nuclear weapons effects on equipment and the effects of radiation on men. We were human guinea pigs.

“The damage the radiation caused doesn’t stop with the veterans. It is passed on to their descendents. Ionizing radiation causes DNA mutations that can be transmitted to the next generation.”

A Ministry of Defence spokesperson said: “We are grateful to all the servicemen who participated in the British nuclear testing programme. They contributed to important tests that helped to keep our nation secure during the Cold War.

“Any veteran who feels that their health has been affected by their attendance at the tests can apply for compensation through the War Pensions Scheme.”

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.