The man at the heart of the story, Robert Meredith, had been a farm labourer around Dymock and Kempley all his life, but in 1879, aged 77 years, he fell on hard times. He slept rough, staying in barns and under hedgerows. It is reported that he spent the winter months in the Newent workhouse.

On October 4 1879, he received an order from Mr Nunn, the Relieving Officer, for his admission to the Newent Workhouse. The government’s intention in 1834 was to make the experience of being in a workhouse worse than the life of the poorest labourers and discourage dependency on relief.

On the evening of Sunday, October 12 1879, Robert Meredith was with Abraham Eaves, a friend, at his home in Burtons Farm near Dymock, and generally in “good spirits”. Meredith told Eaves he had great objection to going to the workhouse and he would rather drown himself than go there.

The next morning Meredith was discovered dead in the farm granary hanging from a beam. Maurice Carter, the Coroner, convened an inquest with a jury the following Wednesday at the nearby Horseshoe Inn, Broom’s Green. The jury were local men, William Bullock, E Dodd, Thomas Winter, John Onions, Thomas Griffiths, Charles Dubberly, George Whittle, E Underwood, James Wilkins, Henry Parrack, William Sayce and James Mace.

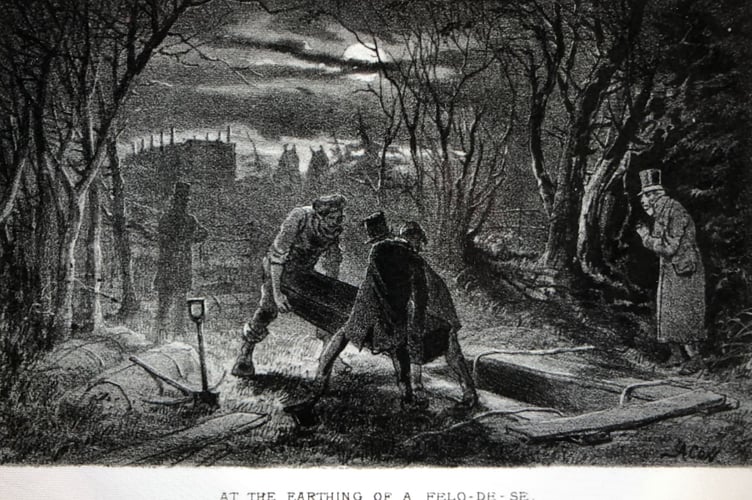

The jury reached a verdict of felo de se, a very old common law that meant that Meredith was considered of sound mind rather that temporarily insane. The outcome was that the deceased be buried without ceremony in the churchyard at Dymock between the hours of 9pm and midnight and within 24 hours.

In Christian orthodoxy suicide was equated with refusing to submit to God’s will; having created life, God alone determined when you left the world.

The lack of a Christian burial, the haunting night-time spectacle of the interment and the shame on the memory of the deceased and their family caused juries to be increasingly reluctant to reach the verdict.

Other notable local cases included:

Clara Jones of Lydney

Clara Jones, aged 23 years worked at the tinplate works. After a night dancing she killed herself with an overdose of laudanum in February 1864. She was described as ‘respectable character’ and had written a suicide note based on her distress at a broken engagement. The jury that met in ‘The Albert’, Newerne, returned a verdict of felo de se. Mr Teague, the coroner, gave an order for her to be buried the same night between nine and twelve o’clock, and it was reported that: “The case caused a great sensation in the neighbourhood, and the deceased was followed to the grave by a very large number of respectable people … between two and three hundred persons were in the churchyard awaiting the appearance of the melancholy spectacle of a fellow creature being cast into the grave without the rites of a Christian burial.”

Mary Maddox of Viney Hill

Two years later, in July 1866, Mary Maddox aged 18 years, wrote to her sister that her mother was haranguing her, bequeathing her sister all her property and saying she was going to poison herself. Anticipating a verdict of felo de se, she told her sister she should not bother coming to her funeral as she would be “put under ground at midnight”. She went to Lydney, posted the letter, bought laudanum, and returned home to kill herself.

Mr Teague, the coroner, reminded the jury that the act itself was not an indication of insanity. But after retiring in private the jury returned a verdict that she had destroyed herself while temporarily insane. There was a growing popular view that the act of suicide was irrational and indicative of insanity.

Thomas Morgan of Joyford

There was no forgiveness in the case of a boy aged 14 years who lived at Joyford, near Coleford. Thomas Morgan worked as a carter with his father, a collier. He made hay in a field at Berry Hill with his father in July 1872. At home in the evening, after refusing to undertake a task for his mother, he left. An hour later he was discovered, hanged in a hedge.

The young Thomas lived in very hard conditions. He attended school for only one year when he was six years old. He had never been in a church or baptised. Evidence was given that the boy was obstinate and afraid of his father. Maurice Carter, the coroner was enraged at the condition of the family. He declared he had never met with a more miserable character in his life which was a consequence of his filthy and disgraceful home and his conclusion was reported as follows:

“the father and mother and four children – one son aged 18 years old – sleeping together without a bed stead and upon frog grass, covered with rags, the room not having a superficial area sufficient for a pig. The children were uneducated and perfectly heathenish, and it seemed incredible that in Christian England a case so shocking could be found.”

Carter recommended the Monmouth Union should demolish the home under the Nuisance and Removal Act as the state of things could only lead to disease, misery and immorality.

The jury returned a verdict of felo de se and Thomas was buried at midnight at ‘Berry burial-ground’ in the presence of a large but silent assemblage.

Maurice Carter was the son of a solicitor and nephew of Richard Carter, Mayor of Gloucester. His family had a long involvement in execution of the Poor Law. He came to Newnham to practise law when he was 22 years of age, in 1848. Two years later he was appointed Clerk to the Westbury on Severn Board of Guardians responsible for the Poor Law and managing the Westbury workhouse, a post he held until 1903. He was Clerk to the Newnham Justices in 1863, a post he held for 42 years, and in 1868, the post of Coroner which he held for 39 years. Carter had a hugely influential position over life and death in the Forest of Dean particularly for the old, sick, disabled and unemployed.

Fanny Williams

In May 1878, the same year as the Meredith suicide, Carter convened an inquest in the Newent Workhouse board room to consider the death of Fanny Williams. She drowned on 17 May in the canal at Malswick. Witnesses reported her being drunk when she lost her job as a chamber maid at the Royal Hotel Cheltenham. She later went to Hereford, drank more alcohol and despite friends’ attempts to return her to her family she was seen wandering near the canal before she was found drowned. Her declaration to several friends that they would never see her again was taken as evidence of her suicidal intent.

Carter told the jury “drunkenness was not insanity” and that he doubted she was of unsound mind. Despite Carter’s direction, the jury decided that Fanny Williams had committed suicide while temporarily insane, probably accelerated by drinking.

Robert Meredith

Carter examined the death of Robert Meredith in October 1879. In summing up he told the jury: “That the presumption of the law was that every person knew the difference between right and wrong.”

The Ross Gazette reported the inquest and the scene at St Mary’s Church at 11.45pm that evening where Meredith was buried, as more like a “dog than a human being”.

Meredith’s body had been conveyed to St Mary’s in a cart of straw covered by a sheet. In attendance were the churchwardens, the sexton, a farmer, a policeman and about fifteen villagers. When at the church, the body was tipped out and carried to the grave by four men with a rope around the legs and neck. The head, naked legs and grey hairs of Meredith were visible. The owner, presumably someone from the farm, asked for the return of the sheet and so the naked body was put in the grave. There was no burial service and the grave lay in a north to south position and not the customary east and west.

The burial was condemned as an uncivilised act and the assessment that followed was unusually damning for a local newspaper: “We cannot too strongly condemn such a barbarous custom – this heaping insult and ignominy upon a senseless dead body. The sooner an enactment of this kind is removed from the statute book, the sooner it will remove a stigma upon the memory of the imbecile promoters.”

The gothic image of Robert Meredith’s interment was seized upon by other newspapers. The Gloucester Citizen picked up the growing story under the headline: “A Real Burial Scandal”. This attracted national attention. The Daily Telegraph reminded the public of the archaic law of felo de se, noting that there was no statute requiring that the corpse should be “unshrouded and uncoffined”. It pointed an accusing finger at the parochial authorities of Dymock. It observed that Meredith had even been denied the coffin and hearse, afforded to those who died in the workhouse.

A regional London newspaper wrote: “Did they ever suck in human milk down at Dymock, in Gloucestershire? Are they all brute beasts? Are there no women there? Not one man among them? Nothing human? A poor broken-down old man of nearly eighty years of age, friendless and with no prospect before him but the workhouse, in a state of despair, flung his life away. At the grave, the corpse was lowered, all but naked, by ropes passed under the neck and head, with no more respect, no more ceremony, than though it had been the carcase of a dog.”

There was increasing public pressure to find someone accountable for the treatment of Robert Meredith after his death. The Newent Board of Guardians on 5 November 1879 responded claiming that they “regretted the way the old man was buried”.

The Dymock Burial Scandal

On the 22 November the Citizen ran another story under the Dymock Burial Scandal headline describing how six men employed at a nearby colliery had been found in the garden of one of the jurymen from the inquest. When challenged they stated they were digging a grave for the juryman, who promptly fled his home.

Three years later the government passed the Interments (Felo de Se) Act of 1882. This allowed a person whose death was criminal suicide to be buried in a churchyard at any hour, and with the usual religious rites. It was not until the Suicide Act of 1961 that felo de se was finally abolished.

After the case there was antipathy towards Dymock residents. This reportedly extended to carters from Dymock covering the name ‘Dymock’ from their signage when travelling in the Forest lest it provoked stones being hurled at them.

The enduring bitterness towards Dymock was captured by FW Harvey in his reflections in Warning.

And if your feet so far should stray

As Dymock, lest some hurt,

Befall you, make no mention of

The man without a shirt.

Today, the Dymock ‘poets’ walk’ meanders around the churchyard where George Meredith was buried.

When life is difficult, Samaritans are here – day or night, 365 days a year. You can call them for free on 116 123, email them at [email protected], or visit samaritans.org to find your nearest branch.

.jpeg?width=209&height=140&crop=209:145,smart&quality=75)

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.