In 1601, under the Elizabethan Poor Law the state assumed responsibility for the maintenance of the poor. ‘Outdoor relief’ was paid either in money or kind. A poorhouse was opened in each parish, funded through the collection of a poor rate from local residents.

In charge of this process were Overseers of the Poor. In Westbury-on-Severn, in 1675, Church House, on the west side of the churchyard, was used as a poorhouse.

Westbury Workhouse

The 1780s saw high food prices and low wages. Even men in work were often too poor to feed their families. In Westbury, it was resolved in 1789 to build a parish workhouse, one of eight that would be built in the Forest of Dean. Wealthy property owners John Colchester, of Westbury Court, John Boughton, a merchant of Broadoak, and William and Joseph Cadle were amongst the parish representatives who borrowed £300 to build the workhouse on parish lands where Colchester Close is now.

In 1792, Thomas Witles, a weaver, was appointed to inspect and manage the poor of the workhouse for a year and he and his family were given accommodation, a salary of £15.15s per year, and malt and hops for his brewing. In 1795, a Gloucester firm was contracted to employ all the paupers to make pins at the workhouse. In 1803 the ten occupants of the workhouse earned £25 making pins.

In 1795 the Speenhamland System set a scale based on the price of bread to bring a working man’s income up to ‘the breadline.’ Some employers underpaid workers knowing their wages would be brought up to the ‘breadline’ by the parish. This led to an era of deterrent workhouses – spearheaded by a retired sea captain, George Nicholls who said: “I wish to see the poorhouse looked to with dread by our labouring classes and the reproach for being an inmate of it extend downwards from father to son.”

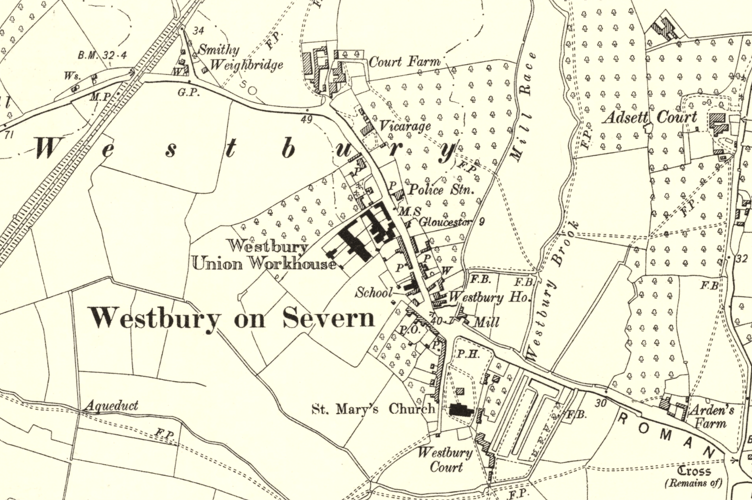

The small parish workhouses were replaced with large Union workhouses designed to accommodate several hundred people. The Westbury-on-Severn Union consisted of 14 parishes: Abenhall, Awre, Blaisdon, Bulley, Churcham, Flaxley, Huntley, Littledean, Longhope, Minsterworth, Mitcheldean, Newnham, Westbury and, later, East Dean. There were other Union workhouses at Newent, Ross and Monmouth.

The Westbury Board of Guardians, elected by the ratepayers, had its first meeting on 29 September 1835 under the chairmanship of Reverend Charles Crawley, the Vicar of Hartpury and one of the Crawley-Boeveys of Flaxley Abbey.

The Westbury workhouse had to accommodate between 60 and 80 people. The existing building was not large enough and initially some people had to be placed in Littledean Workhouse. There was no provision for vagrants who sought shelter and there were instances of tramps dying from exposure or starvation after being turned away.

Workhouse conditions

On arrival the poor were stripped of their clothes (and their dignity) and any private possessions. They were made to wear rough prison-style uniforms and discipline was rigid. Sanitation arrangements were basic. Meals had to be eaten in silence sitting in rows and inmates were only allowed out of the workhouse with permission.

In winter, it was cold. A thin mattress and one blanket on iron bedsteads in large dormitories meant there was little comfort or privacy. The workhouse food ration was less than that allotted to prisoners. Inmates were expected to work ten hours a day for six days a week.

Inmates who broke the rules were flogged, birched, denied food or put in solitary confinement. Families were split up although children under the age of seven could usually remain with their mothers.

The day-to-day running of the house was done by John James and George Evans, for up to 30 years.

The account of the Board of Guardians’ dinner in 1837 illustrates how far apart the Guardians were from those who came under their control.

The dinner was held at the Bear Inn in Newnham to present Reverend Crawley with an elegant silver tea urn, which cost upwards of 100 guineas, (about £10,000 in today’s money) as a mark of their respect and esteem. 71 people attended and a eulogy was delivered on the “ability, assiduity and courteous behaviour” of the chairman. The Board had proved itself “really beneficial to the ratepayers” and: “a considerate and humane one in the management of those whose poverty had placed them under its control.”

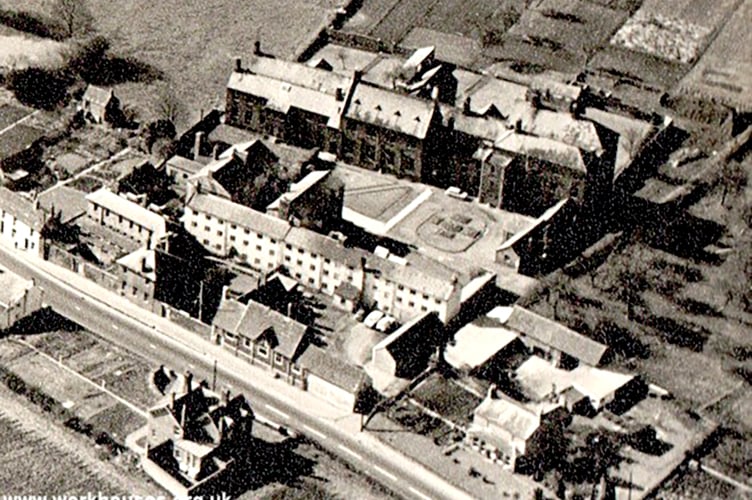

On buying the old parish workhouse for £1,200 in 1869, the Board of Guardians substantially altered and extended it to hold 300 people. Fronting the road was the boardroom, porter’s lodge, vagrant wards and stables, with the Master’s quarters, day rooms and kitchens behind them. Behind that was a huge new two-storey block which contained the dining hall a chapel above, schoolrooms, day rooms and dormitories.

In 1882 George and Julia Evans were appointed as Master and Matron. They were still there 30 years later at the time of the 1911 census.

Vagrants were housed in cells in the old part of the workhouse. In 1895 a Local Government Board Inspector described them as “a disgrace to civilisation”. The Board of Guardians disagreed and argued that they had always passed inspection before.

In January 1896, there was a smallpox outbreak in Bollow, a tything of Westbury, which caused fears about what might happen if this spread to the workhouse. The Board of Guardians installed an isolation hut at Gunns Mill and a six-year-old child was admitted to this little hospital. Sadly the child died, but this measure stopped the disease from spreading. The Board of Guardians was, however, berated by the Local Government Board for not enforcing smallpox vaccination. Lice and fleas were also a problem and children’s hair was often shaved off, although this was also sometimes used as a humiliating punishment, especially on little girls.

Workhouse Education

The 1834 Poor Law Act required that children receive three hours education per day. In Westbury, in 1848, Henry Grindon was appointed schoolmaster for the Union Workhouse by Reverend Wetherall, the Vicar of Westbury.

In 1858, the Matron’s daughter, Susan Goyen became schoolmistress and paid £20 per annum. In 1870 a new Education Act meant that children from the workhouse had to attend the local Board School. There were a lot of absences from Westbury School due to outbreaks of various illnesses, often originating from the workhouse children. This caused complaints from village parents, who felt that their children were being put at risk. In September 1898, there was a serious epidemic of diphtheria and the school had to be closed for eight weeks. Three village children died. In 1907, 37 workhouse children were away for a month owing to another outbreak of diphtheria, believed to be due to defective drains.

The harsh regime of the workhouse softened at Christmas, when a tea party, a Christmas tree with toys for the children and some entertainment in the Dining Hall were organised by staff. Mitcheldean Band came along one year, and on other occasions there were comic songs, concerts by the children of Walmore Hill School, entertainment by the family and friends of Mr and Mrs Colchester-Wemyss and some carol singing.

Outdoor relief

Although many paupers were in the workhouse, ‘outdoor relief’ was still being paid and in 1876 the Board of Guardians set out rules as to who would be entitled to this. The Guardians were not happy with the cost and in 1889 they passed a resolution that: “Out relief, as generally administered, tends to create poverty and destroy that feeling of self-dependence which should be possessed by the poorer classes.”

Welfare State

In the 20th Century, outdoor relief was gradually replaced by state pensions and benefits. Friendly societies and trade unions provided help for their members.

From 1904, birth certificates of children born in the workhouse gave their address as 1 High Street, Westbury-on-Severn to protect them from disadvantage in later life.

Workhouses were officially abolished in 1929, however, many inmates had nowhere else to live and some were unable to adjust to life outside. The care of some 60 orphans was transferred to local councils and were boarded out in private homes. The last workhouse child left Westbury School in 1934, but I spoke to a Westbury resident who started school there in 1938 and she remembered children from the workhouse coming to school. She said they were avoided by the other children because they smelt so strongly of carbolic.

Westbury Workhouses became a ‘county infirmary.’ Uniforms were no longer worn, there was better food and heating and a sitting room with easy chairs. Inmates were free to come and go and the practice of splitting families was stopped. Discipline remained strict, but punishments were less harsh.

Gwen Partridge, who worked at the infirmary for thirty years, recalls that her time was divided between caring for the elderly, the sick and unmarried mothers who came to give birth. This was apparently known locally as ‘going over the hill’. Tramps still turned up looking for somewhere to stay for the night, but former infirmary staff member in the 1950s, Mary Baker, recalls some being turned away. Tramps were forced to break stone after which they got a bed, a haircut and a good breakfast before carrying on to Gloucester.

Gwen’s stories of the unmarried mothers are perhaps the saddest. Some of them had themselves been born in the workhouse and felt a terrible sense of shame that they were giving birth there too. Joyce Latham in her book about life as a girl in the Forest of Dean in the 1940s, Whistling in the Dark, describes how she was born to her unmarried mother in Westbury Workhouse in 1932. Her grandmother had described it as a: “grim sort of place, all gloomy and bare walls”.

Joyce was named after a nurse who had been very kind to her mother. Gwen remembers one little boy for whom no home could be found. The matron felt that any adoptive parents should be told that the baby’s father was also his grandfather – after which any potential adoptive parents did not proceed.

Gwen, who had no formal nursing training, loved her job and talked with pride about the care they gave.

During the Second World War the infirmary was used to treat wounded soldiers, who came via Birmingham and brought on stretchers from Grange Court Station by the Home Guard. They were nursed on a ward which became known as Birmingham Ward.

In 1948, the National Assistance Act put local authorities in charge of providing residential care for those who needed it. The Westbury County Infirmary became the Dean Hall Hostel, but after local objections it was changed to Westbury Hall.

Mary Baker, recalls some of the long-term residents. Some had been born in the workhouse and remained there all their lives. She particularly remembers Elsie Cook, who was sent to the workhouse by her older sister when she was 21. She used to go to the village shop to make purchases for other residents and she remained until the Infirmary closed, when she moved to Westbury Court.

In 1957, the WI History reported that it held about 120 old people and 42 sick hospital cases and: “The old people from the Hall are often seen in the village and look perfectly happy. It is a very well organised institution and the Master and Matron are keenly interested in their work.”

Eleven years later, the elderly patients transferred to Westbury Court Care Home and the hospital patients moved to the Dilke Hospital. Mary Baker says that many of them missed the Infirmary and said that they wished they could go back.

Westbury Hall finally closed in the autumn of 1968 and the building was demolished in 1970. There is now no trace of its existence left in Colchester Close but, not far away, in Stantway Lane, the flagstones from the workhouse kitchen form a garden path.

The full article about Westbury Workhouse is in the current New Regard available from https://forestofdeanhistory.org.uk and local outlets.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.